“It is hard to know any longer if women still exist, if they will always exist, if there should be women at all, what place they hold in this world, what place they should hold.” — Simone de Beauvoir

There are instructions for me:

- Please say you are here for the performance in Apartment 2C (guests of Barbara Grill and Brian Drolet). The house opens at 7:45. NO LATE SEATING.

- Once the performance begins, late comers will not be allowed up to the performance space and will be turned away by the doorman.

- It is important that we keep all coats and bags out of the performance space. There will be a coat rack outside the apartment door before you enter, and a place for bags inside the apartment when you check in.

But my train is running late

And I remember the invite said “NO LATE SEATING.” I find a taxi outside the subway station. “I’m running behind. Can we find a street with less traffic?” We travel north on 8th Avenue and cross Central Park on 86th Street. I arrive on time.

The doorman tells me to take the elevator to the second floor. Outside the apartment door, I remember to take my jacket off and hang it on the coat rack. I claim my ticket from the man with the iPad at the front door. He tells me where to put my bag, on the table for bags inside the apartment.

“Is it okay if I use the bathroom?” A different man directs me to the bathroom in a hallway past the kitchen.

The house manager tells me I can sit in any of the chairs lining the perimeter of the living room in the apartment. There are approximately 20 other people in the room.

I open the notebook on my lap. I am ready to take notes for the review I am going to write.

The performance begins:

Seven female dancers enter and begin interacting with the furniture in the room. One sweeps the baseboard with her hand, one uses her finger to scratch a shelf in the bookcase, one drags a foot across the surface of the rug. Their actions are diligent and gain intensity over time. Scrubbing the floor in a wider motion, scratching with more pressure, sweeping with quicker and shorter movements. We watch them: limbs and bodies against the structure of the house. Hear their heavy breathing and groaning.

The dancers interact with the space that we share, sweeping the carpet underneath a chair someone is sitting on, crouching to brush away dust on the fireplace mantle behind someone’s back. I can feel the friction, the noise that their bodies are generating.

With their heads down, still maintaining a narrow focus on the task in front of them, they begin to yell:

“I really want to get in there!”

“I’ve been doing this all week”

“It’s tiring.”

“It’s too much.”

“I’m not going to be able to finish this.”

Their torsos start convulsing. Their energy is wild, frenetic.

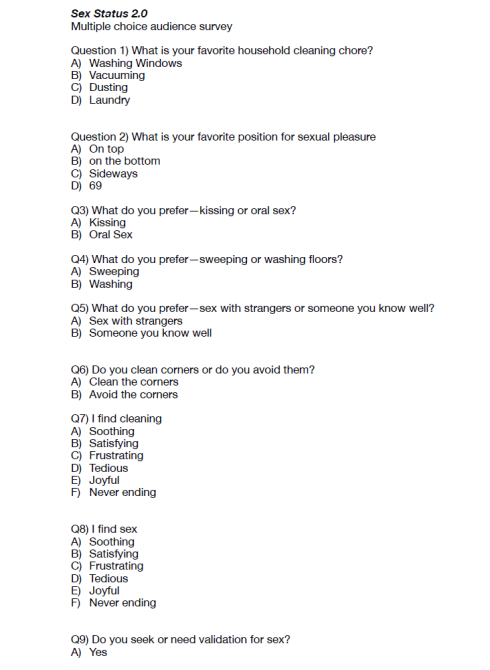

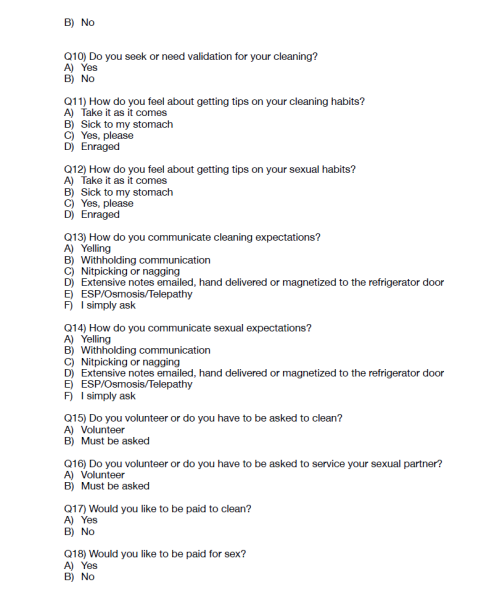

The first act ends. Carrie Ahern, dancer and choreographer of Sex Status 2.0, walks to the center of the room and puts on a pair of glasses. She announces that there’s going to be a multiple choice audience Sex/Cleaning Survey. She will ask us to raise our hands and her assistant (another dancer) will record and collect the data. Ahearn tells us that all attendees will be sent an email after the performance with an overview and analysis of the survey results.

Beyond drawing out a relationship between sex and cleaning, the survey’s questions elicit responses from the audience, activating our individual memories and attitudes about domestic labor and sex. It is complicated to interrogate a person’s relationship with sex; it is even more complicated when the emotion of that relationship becomes a part of the performance.

Eventually all of the dancers will return to the room and their bodies will regain the outward focus of the room. In one section, they’ll approach audience members and ask for their consent to touch the dancers in a way they enjoy, to stroke the length of their body from their head all the way down the left side of their body, or to trace letters on their back. In another section, they will gaze at audience members, making extended eye contact while moving their bodies in different ways, at times both playful and provocative.

Eventually all of the dancers will return to the room and their bodies will regain the outward focus of the room. In one section, they’ll approach audience members and ask for their consent to touch the dancers in a way they enjoy, to stroke the length of their body from their head all the way down the left side of their body, or to trace letters on their back. In another section, they will gaze at audience members, making extended eye contact while moving their bodies in different ways, at times both playful and provocative.

My inward focus remains on the survey. I recall that the movements of my body are always watched. Visibility makes me valuable. I work hard to be seen and this labor is pleasurable to others. My work never ends. One of my fears, which I prefer to leave unexamined, is now present at this dance performance on a Saturday evening in a private apartment on the Upper East Side. Someday I will not be seen as attractive to men. Will I be able to feel pleasure when I am no longer the subject of someone else’s pleasure?

Do you clean corners or do you avoid them?

It was getting late and it was going to take me a long time to get back to my apartment in Flatbush from Clinton Hill. My friend offered to let me stay over. But I had to work the next day and I was wearing a cropped sweatshirt.

“I can’t wear this to work.”

“Why?”

“Uhhhh, because it shows my stomach. I can pretty much wear anything to work, but I try to have all my skin covered. Everyone dresses pretty modestly. I guess I could go to H&M and buy something in the morning.”

“That seems pretty crazy.”

“It’s super close to my office and I could get something for cheap.”

“Ack, I have all of those shopping bags. I can’t go into work with those in the morning.”

“Why would anyone care if you come into work with bags?!?”

Because I believe myself to be constantly watched. I have been taught that my credibility lies in my appearance. More important than my performance at work is the appearance of my performance.

What do you prefer–sex with strangers or with someone you know well?

I danced with the guy for a couple of hours at a bar in Bushwick. Before I left to go home with my friends, he asked for my phone number.

I noticed that he wore a lot of streetwear in his Instagram photos. I already owned a cropped velour hoodie from Adidas. At the time, the matching track pants had seemed too expensive ($80.00). But I wanted to wear them when I went over to his house, so I went back and bought them. He told me that the pants looked good on me as I was getting dressed in the morning and I felt validated in my decision to spend so much money on them.

Do you seek or need validation for sex?

While we faced the barre, our ballet teacher Karen would walk by and touch the base of our spines. When she did this to me, it cued my butt to draw downwards and my stomach to draw upwards. She called this correction “tucking our tails” and it eliminated any protrusion of the butt or the belly. Although we faced the barre, this correction was always meant to be observed in the mirror at the front of the room, where we would watch our profiles as we performed warm up exercises, aware not of how we looked but of how we were seen.

The inspiration for Sex Status 2.0 is Carrie Ahearn’s reading of Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex. Beauvoir says, “Few tasks are more like the torture of Sisyphus than housework, with its endless repetition. The clean becomes soiled, the soiled is made clean, over and over, day after day.”

In a New York Times interview about her show, Ahearn spoke to Beauvoir’s ideas about housekeeping: “Pushing into the negative is work that’s never done — it will never be finished. In some ways, it becomes invisible almost the moment it’s finished.”

Women become invisible at almost the same exact moment they are seen. As soon as they become the object of someone else’s vision, they must be at work again, devising new ways of commanding attention. Like work that negates itself, recognition via being recognized is negative recognition.

Women’s bodies now exist outside the home and are in more positions of power. This has resulted in a greater level of visibility. Ahearn makes the point that in today’s political climate, it is imperative that women choose the ways in which they want to be seen.

Leave a comment

Comments feed for this article